A Mother’s Death, a Continent’s Burden: Tackling NTDs in Africa

Neglected tropical diseases cause not only suffering and disability but also deep social rejection—leaving millions behind.

Two years ago, in a village in Côte d’Ivoire, tragedy struck the family of Mathieu Okoma Agoa. His mother, who had leprosy, lost her home when it was burned down by neighbours. One week later, she passed away.

Some people in the village celebrated her death, believing that “the evil was gone.” Her only ‘crime’ was having a disease that many people still do not understand. Leprosy, which causes visible deformities and physical suffering, also leads to deep social rejection and discrimination.

Her story, as reported by Al Jazeera, is an example of how neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) affect not just the body, but also the dignity and lives of individuals.

NTDs are a group of 25 diseases or conditions that primarily affect people living in poor, rural areas of tropical regions. These include, among others, leprosy, schistosomiasis, dengue fever, Buruli ulcer, onchocerciasis, and soil-transmitted worm infections.

More than one billion people worldwide are affected, with Africa carrying approximately 40% of this burden. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 600 million people in Africa require treatment for at least one NTD. In many countries across the continent, five or more NTDs are found in the same areas, compounding the problem.

At least four NTDs have been identified in 47 African countries, spanning West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and parts of North and Southern Africa

The health impact of NTDs is immense. Every year, these diseases cause an estimated 120,000 deaths and result in more than 14 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost globally. Yet the consequences go far beyond the medical. People living with NTDs often face poverty, reduced productivity, and disrupted education.

These diseases trap families and communities in a cycle of poverty. Globally, the economic cost of NTDs is estimated at more than 33 billion US dollars each year. This burden makes it more difficult for African nations to achieve crucial global goals such as ending poverty (SDG 1) and ensuring good health and wellbeing for all (SDG 3).

One of the most pressing challenges in the fight against NTDs in Africa is the chronic underfunding of health systems. The situation is deteriorated further as the United States government—a major donor through USAID and other agencies—decided to significantly cut foreign aid to Africa during Donald Trump’s second term as President. These reductions are already severely affecting NTD-related programmes, making it increasingly difficult for partner organisations to sustain prevention and treatment efforts.

With international aid shrinking, African governments now face the difficult task of continuing disease control with fewer resources. Many are already struggling to provide basic healthcare, and now they are being asked to do more with less.

Another critical challenge is the weakness of data systems and poor disease surveillance. In several countries, there is insufficient data on how many people are affected by NTDs or which regions require the most urgent intervention. Without accurate and timely data, it is difficult to plan effectively or measure progress. In West Africa, for instance, many nations have yet to eliminate a single NTD, and tracking progress remains difficult due to inadequate reporting mechanisms.

Cultural beliefs and stigma further complicate the fight. As in the case of Mr Agoa’s mother, individuals suffering from conditions such as leprosy or female genital schistosomiasis are often marginalised or even subjected to violence. Fear, misinformation, and shame discourage people from seeking treatment, allowing diseases to persist and spread.

Despite these serious obstacles, new opportunities are emerging. One of the most promising is the application of digital tools and modern technologies. Innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI), mobile health applications, drones, telemedicine, and wearable health sensors are revolutionising disease detection, treatment, and monitoring.

For example, researchers are now using AI to design better drugs and understand the mechanisms of existing treatments like praziquantel. AI is also aiding in tracking the evolution of parasites, a key step in identifying drug resistance early.

In one initiative, scientists working with the University of Oxford are developing an AI-powered tool to diagnose female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) by analysing images of cervical lesions. This could help health workers differentiate FGS from sexually transmitted infections, enabling quicker and more accurate treatment.

Technology is also improving access to remote communities. Mobile clinics and telemedicine make it possible for healthcare providers to deliver services without being physically present. Drones are being used to transport medical supplies to hard-to-reach areas, and mobile apps and wearables help patients report symptoms and monitor their own health in real time.

The African Union, through the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), is stepping up its leadership role. In 2024, it launched a new blueprint to combat NTDs, focusing on health system strengthening, greater political support, measurable targets, and leveraging technology for monitoring. The WHO is also supporting regional research through programmes that train public health workers in countries like Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Senegal to conduct operational research and improve local NTD responses.

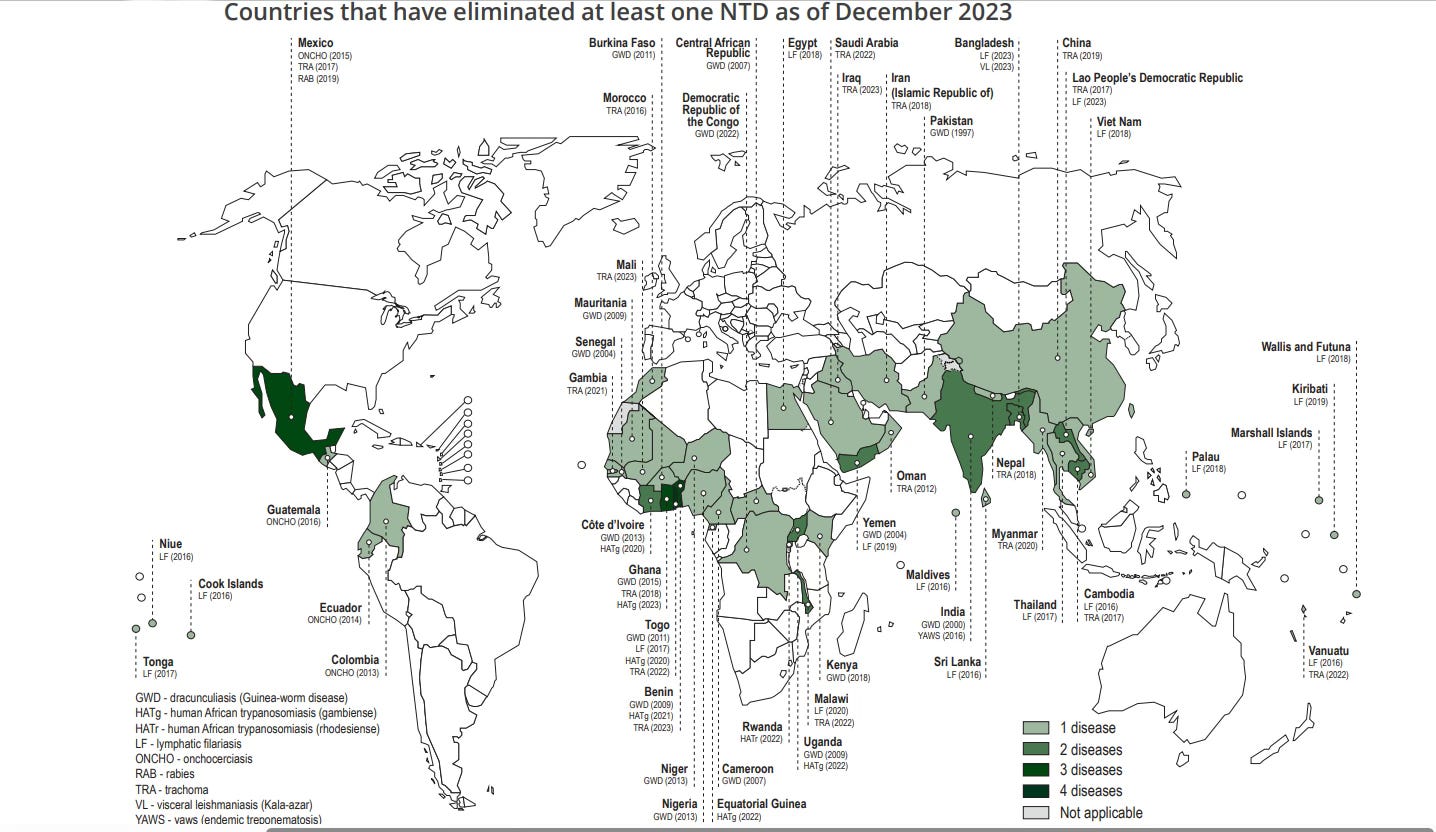

Source: 2024 WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases

To defeat NTDs, Africa requires a united and sustained effort. Governments, scientists, community leaders, and international partners must work collaboratively to ensure that no one is left behind. By investing in resilient health systems, embracing technology, and combating stigma, the continent has a chance to change the story.

Neglected Tropical Diseases may be widespread, but with commitment, innovation, and compassion, they need not be permanent. The tragic story of Mr Agoa’s mother is a painful reminder of what is at stake. But it also serves as a call to action—to build a future in which no one suffers or dies simply because they are poor, ill, and forgotten.

Cédric Mbavu is a PhD candidate specialising in the field of health economics at Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM) in Hamburg, Germany.

—END—