Africans Climate Change Awareness Gap

It's important that Africans understand what causes climate change, who is responsible and how it can be tackled.

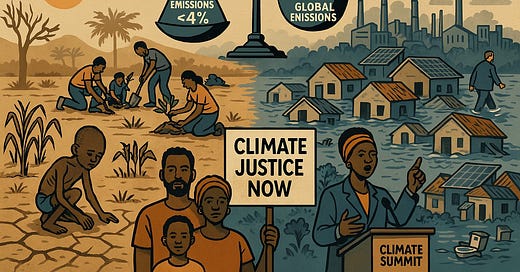

From extreme heat waves to devastating floods, Africa has suffered some of the worst effects of climate change in recent years–you’ve probably experienced some of these impacts personally or within your community.

But this raises a central question: who is responsible for climate change in Africa, and who should fix it?

That question is at the heart of a paper published in Communications, Earth & Environment. We know that climate change is primarily driven by greenhouse gas emissions that trap heat in the atmosphere. And we also know that fossil fuels–coal, oil, and gas–are the biggest contributors, responsible for over 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Ordinary Africans are paying and will continue to pay heavily due to climate change. It is estimated that by 2030 up to 118 million extremely poor people will be exposed to drought, floods and extreme heat in Africa.

Floods and poor sanitation caused by extreme weather makes it easier for diseases to spread in sub-Saharan Africa. This has led to more cases of illnesses like malaria, dengue fever, Lassa fever, and Ebola. Rising sea levels are also making clean water harder to find, causing more water-related diseases like diarrhea, which is one of the top killers on the continent.

Extreme weather is damaging crops and water sources, making it harder for people to get enough food and clean water–leading to hunger and malnutrition that kills about 1.7 million people in Africa every year.

Despite bearing the brunt of climate change, Africa contributes less than 4% of global emissions. Yet, according to the Communications, Earth & Environment paper—drawing on Afrobarometer survey data—most Africans believe the responsibility to address climate change lies at home.

“Almost half (45%) of Africans who have heard of climate change believe their own government is primarily responsible for addressing it and reducing its impacts,” the paper states. “By comparison, 30% attribute primary responsibility to everyday Africans themselves, while only 13% and 8% place the blame on rich countries and business and industry, respectively.”

Interestingly, citizens of island nations like Mauritius, Seychelles, and Cabo Verde—who are more aware of sea level rise—are more likely to point fingers at historical emitters. The study also shows that access to newer media, such as social media and the internet, tends to shift blame away from national governments and toward businesses and industries.

To me, the findings are both obvious and somewhat encouraging.

It's obvious, because climate change is a complex subject, especially for less-educated or rural populations. I wouldn’t expect the average African to fully grasp who is responsible for climate change. Yet it’s encouraging that nearly a third believe that ordinary Africans must take the lead in tackling this crisis.

However, the biggest stumbling block remains the cost of climate action. Africa needs an estimated $277 billion annually until 2030 to effectively respond to climate change—but currently receives only about $30 billion a year.

To meet this challenge, Africa must collectively demand accountability from those responsible–the Global North–and compel them to finance the continent’s climate agenda. We need a continent that is not just aware, but outraged, and ready to push back against climate injustice.

At the same time, this does not absolve African governments of responsibility. Many have failed to address unplanned urbanisation that leads to frequent flooding, or to enforce laws protecting wetlands and forests. There’s a lot of work to be done on both ends.

Ultimately, for Africa to succeed in this fight, we must first win the battle of awareness. Only then can we unite our 1.3 billion people to demand the financing and justice we deserve.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

“In most African Union member states, children are 18 times more likely to die before their 5th birthday than in other regions,” Africa CDC

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“Our data shows that pro-climate behavior changes, such as driving less or eating less meat, could theoretically cancel out all the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions an average person produces each year,” World Resource Institute, on the most impactful thing you can do for climate change.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Prenatal alcohol exposure and brain development in early childhood: A study in South Africa looked at how drinking alcohol during pregnancy affects children's brain development and learning abilities at ages 6 to 7. The children with prenatal alcohol exposure showed changes in brain structure, including smaller areas in parts of the brain involved in thinking and memory, especially in the region linked to understanding numbers and concepts. These brain changes were connected to poorer performance in skills like math, problem-solving, and memory. [Reference, Alcohol clinical and experimental research]

Polio vaccine dropout risk factors: In sub-Saharan Africa, while about 87% of children aged 12–23 months receive the first dose of the oral polio vaccine (OPV), only 68% complete all three recommended doses, with around 20% dropping out before finishing. The likelihood of full vaccination increases when mothers have some level of education, are older, are married, give birth in health facilities, have access to media, and come from wealthier households. [Reference, PLOS]

Gender disparities in African scientific research: A study on African women researchers reveals they represent only 29.3% of Africa's scientific community, lower than other regions like Europe (39%) and North America (44%). The study examines gender disparities in scientific publications, focusing on differences between social and exact sciences and regional variations between North and Sub-Saharan Africa. From 2010 to 2022, female authorship increased modestly from 29% to 32%, with significant growth in exact sciences, especially in Engineering, Physical Sciences, and Life Sciences. However, progress in social sciences was slower. [Reference, Learned Publishing

—END—