Africa’s climate emergency: the drought that won’t end

A new report, Drought Hotspots 2023–2025, warns that extreme drought conditions, worsened by climate change and the El Niño–La Niña cycle, have devastated wide parts of the African continent.

When I first boarded a plane in my life in 2017, it was for a journalistic reporting trip to Somalia.

What surprised me most was how hot the country was. You couldn’t sleep in a house without an air conditioner because the temperatures were extremely high–even early in the morning. By 10 A.M., it was almost unbearable to stand in the sun for a minute.

Somalia has always been hot. Located near the equator, the country experiences some of the highest temperatures on the African continent. Its landscape–shaped by semi-desert plains and dry winds from the Indian Ocean–has long tested the resilience of its people.

Today, the country is facing a devastating crisis that is no longer just natural, it is being intensified by climate change. And it’s deadly.

According to a new report by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), Somalia is at the epicenter of a growing emergency that stretches across the Horn of Africa to Eastern and Southern Africa.

The report, Drought Hotspots 2023–2025, warns that extreme drought conditions, worsened by climate change and the El Niño–La Niña cycle, have devastated wide parts of the African continent. Regions already vulnerable due to poverty, conflict, and weak infrastructure are now facing a full-scale humanitarian disaster.

From Somalia to Zambia, over 100 million people across Africa have been affected by back-to-back failed rainy seasons, scorched crops, dried-up rivers, and mass displacement.

In Eastern Africa, Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia have endured five consecutive failed rainy seasons. By mid-2025, nearly 23 million people across the region are classified as “highly food insecure.” The report estimates that 43,000 people died in Somalia in 2022 alone due to drought–many of them children.

In Ethiopia, over 10 million people, especially in conflict-affected areas like Tigray and Amhara, are struggling with hunger and lack of clean water. Humanitarian access remains limited, and food aid has been delayed due to bureaucratic reforms and funding shortages.

Pastoralist communities across the Horn have lost millions of livestock, leaving families without food, income, or cultural identity. By February 2025, herders in Uganda’s northeast had begun crossing borders in search of water, echoing the desperation unfolding further east.

Looking further south, the crisis deepens.

A powerful El Niño event in late 2023 brought intense heat and drought across the Zambezi Basin, affecting Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, and Namibia. Maize crops—the region’s staple, have withered. By April 2024, 68 million people across Southern Africa needed food aid.

In Zambia, half the maize crop failed, prices soared, and 30% of the population faced malnutrition.

In Zimbabwe, the corn harvest dropped by 70%, food inflation spiked, and 6 million rural residents needed assistance.

In Malawi, 40% of the population faced hunger, and the government requested over $200 million in emergency aid.

This food crisis was compounded by an energy emergency. With rivers at record lows, hydropower plants shut down. In Zambia, homes and hospitals experienced blackouts of up to 21 hours a day. Dialysis machines stopped. Clinics turned away patients. Small businesses closed. And the economy tanked, Zambia’s currency lost 15% of its value in just six months.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

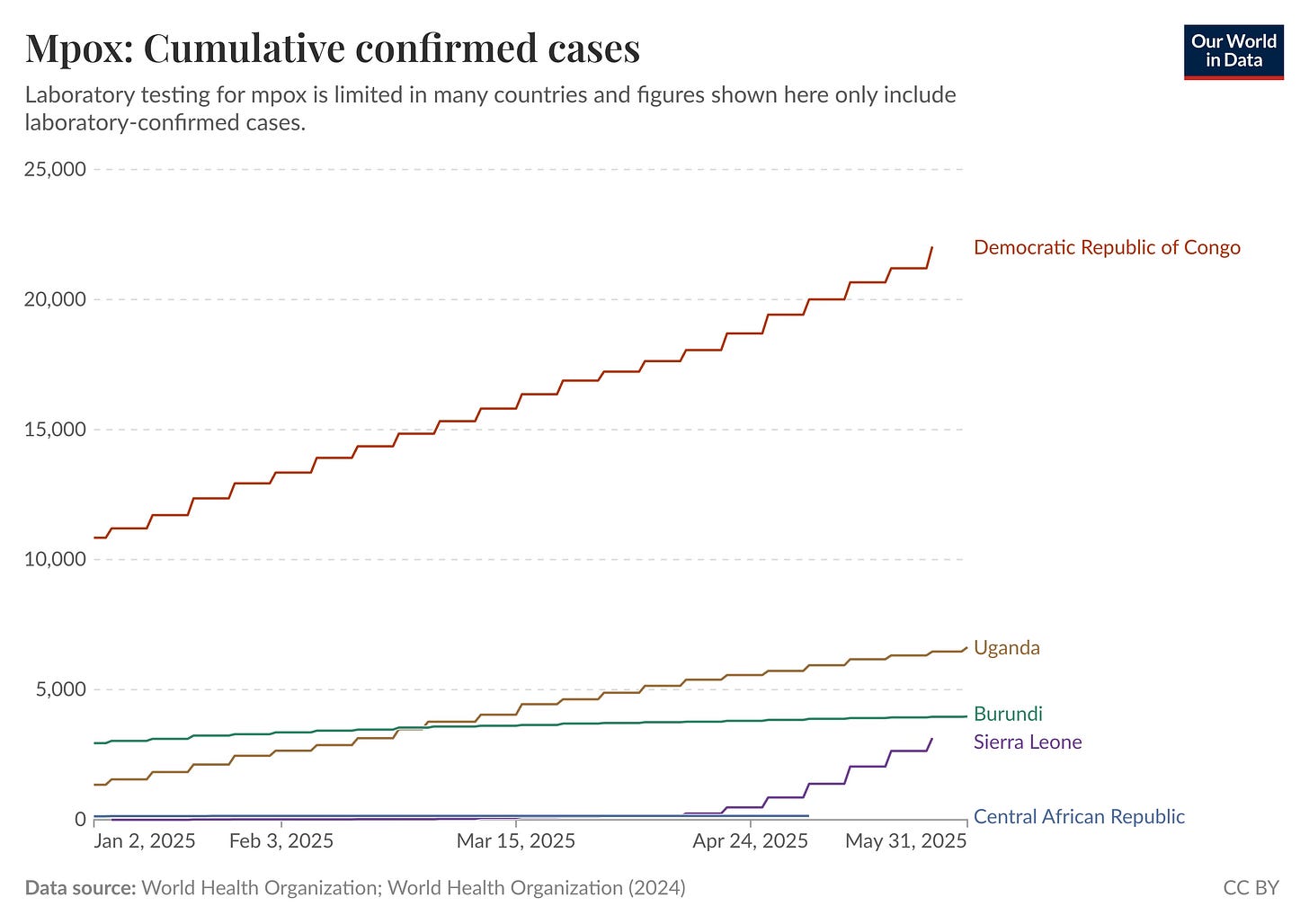

We are halfway through the year, and one epidemic that has dominated headlines in Africa is Mpox. So far, more than 21,000 cases have been recorded across at least 13 countries—already surpassing the 19,738 cases reported throughout all of 2024, according to the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Which country has the most cases? See the graph below.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“They are small countries, with populations of one to two million people, but they have the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world—meaning more adults are living with HIV there than anywhere else. On top of that, with support from the U.S. government, particularly through the PEPFAR program, they have achieved remarkable success in turning around the epidemic over the past 20 years,” Jon Cohen, on travelling to Lesotho and Eswatini to report on the impact of U.S. government funding cuts on the fight against HIV.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Deaths from dirty cooking fuels rising in East Africa: A study which looked at air pollution from household cooking in East Africa between 2010 and 2019 found that more than 134,000 people died in 2019 alone due to inhaling smoke from cooking with wood, charcoal, and kerosene. Most of the deaths were caused by lung infections, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The highest death rates were recorded in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Men were slightly more affected than women, and death numbers increased significantly after 2014. The study warns that if no action is taken, deaths will likely remain high through 2030. People living in poverty and rural areas face the greatest risk. The researchers recommend switching to cleaner fuels and improving ventilation to reduce health risks. [Reference, Scientific Reports]

How African Dust Reveals Earth’s Ancient Climate Changes: Scientists who studied dust in the Pacific Ocean found that some of it traveled all the way from North Africa, not just nearby South America. By tracing special chemical markers in the dust, they discovered that during cold times like the Ice Age, more African dust reached the ocean. This showed that a major rain belt near the equator, called the ITCZ, moved south. When the Earth warmed, the rain belt shifted north, and South American dust became more common. These changes tell us how sensitive our climate is and how African dust helps us understand Earth’s climate history. [Reference, Nature Communications]

A new era for HIV treatment in Africa: injectable hope: A new long-acting injectable HIV treatment, combining lenacapavir and cabotegravir, offers significant hope for people living with HIV in Africa. This treatment could overcome challenges with daily pills, leading to a predicted 19% reduction in HIV-related deaths and an 18% decrease in mother-to-child transmission. It also promises to improve viral control for more individuals. The study found this injectable therapy to be cost-effective, especially if annual costs are kept around $80-$140 per person. Researchers recommend pilot studies to confirm its real-world implementation and ensure broad access. [Reference, Nature Communications]

—END—