After Death, Would You Donate Your Body for Academic Research?

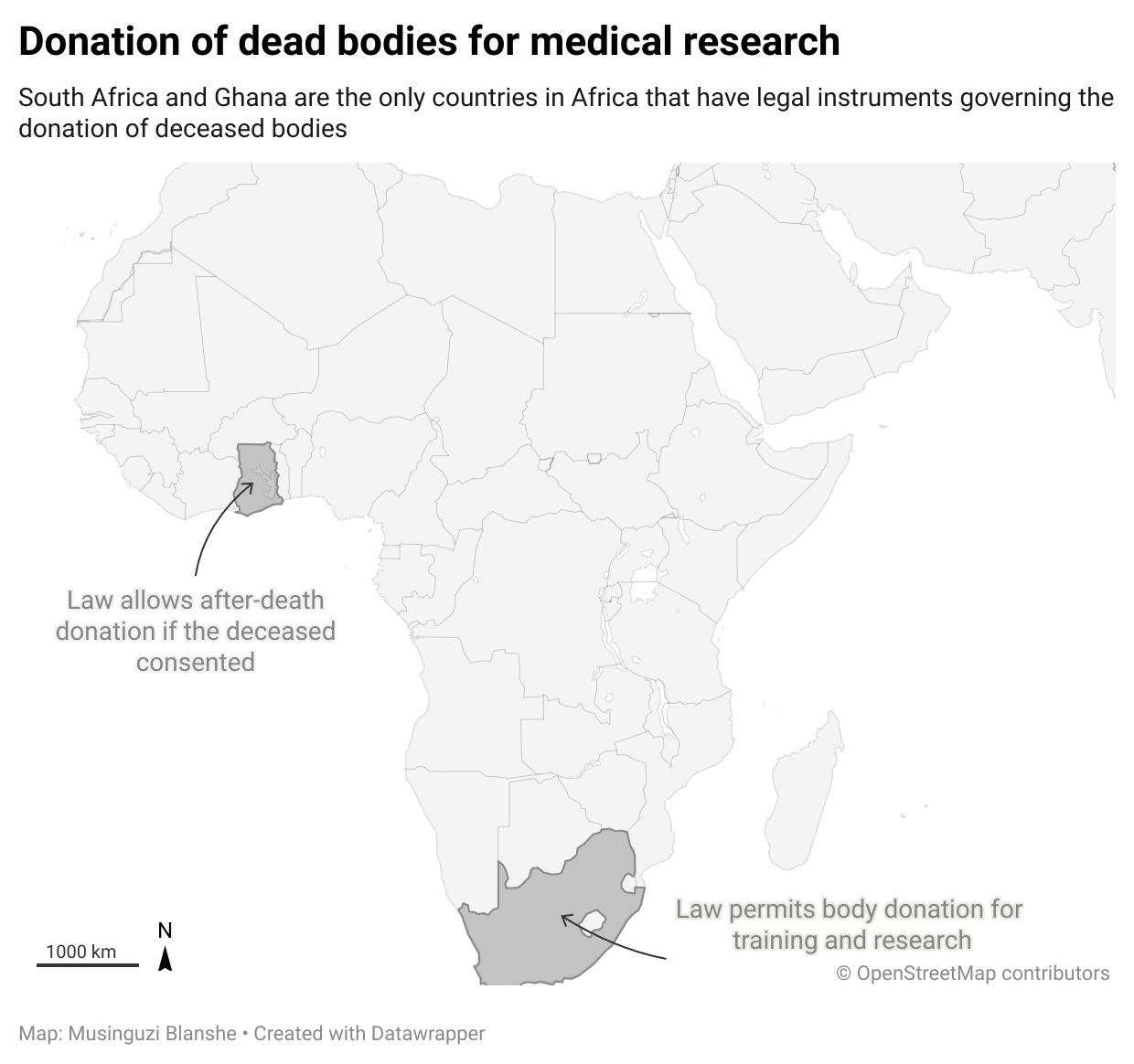

Few body donation programs exist across Africa, with South Africa being a rare exception where the practice is generally accepted.

Africa urgently needs top-tier medical professionals capable of diagnosing and treating a wide range of illnesses. Achieving this goal requires excellent training institutions, advanced equipment, well-equipped hospitals–and, crucially, access to human bodies for medical education and research.

Consider this: would you donate your body after death? And if a loved one expressed that wish, would you honour it?

A study published last month focusing on West Africa found that many institutions continue to depend heavily on unclaimed and unidentified bodies–which they often get without adequate ethical oversight.

The study surveyed anatomy departments at 27 universities across 11 West African countries and revealed the extent of the challenge: “Two of the 27 institutions that responded had body donation programs. These two were different institutions within Ghana. Thus, only one country out of the 11 West African countries represented has body donation programs,” it states.

“Between these two institutions in Ghana, one received an average of five body donations yearly, and the other received two per year. Twenty-three other institutions did not have body donation programs, and two were not sure if any existed at their institution.”

This is not just a West African problem–it is a continental one. Few body donation programs exist across Africa, with South Africa being a rare exception where the practice is generally accepted. In Kenya, one university reported receiving only two body donations over a five-year period.

However, even in South Africa, Black Africans are less likely than others to donate their bodies, perhaps due to cultural beliefs and the country’s political history.

Religious and cultural beliefs pose significant barriers to the establishment of voluntary body donation programs in many African countries. In 2021, Oluwanisola Onigbinde of Nile University of Nigeria noted, “The African culture of burying and burial rites cannot be traded for anything, regardless of the cause of death.”

As a result, educational institutions are often left with little choice but to rely on unclaimed bodies or those of executed individuals, as these are the most readily available. In some countries, there have even been cases where bodies were purchased, either locally or from abroad.

These limitations contribute to the continent’s low research output in the field of anatomy. While 15 institutions across six countries reported using bodies for research, ten of them had no publications or documented findings, according to the study.

The limited output in anatomical research–despite access to cadavers–raises concerns about missed opportunities to advance medical science. Even where human remains are used in educational settings, the research component is frequently absent or goes undocumented.

The study observes that “the literature is very sparse,” and it remains unclear how many peer-reviewed studies or academic publications have resulted from the use of human bodies in medical education on the continent.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“We know that in 2017, our head of state and government did issue a declaration, asking the African Union to work with partners to ensure that we are able to train, recruit, and deploy two million community health workers. Today, we are seeing less than a million community health workers on the continent, meaning that we are seeing less than 50 percent of what we need in terms of community health workforce. Looking at this number, you will agree with me that there's no way you can talk of a strong primary health care that will allow us to achieve universal health care,” Dr. Raji Tajudeen, Acting Deputy Director General at Africa CDC on building Africa’s health workforce. [Reference, Africa CDC Podcast]

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Warming Africa: Emissions and Rising Seas: A study exploring how rising CO₂ and methane emissions in Africa are driving higher temperatures and sea levels–despite the continent contributing the least to global greenhouse gases–found a strong link. Analyzing data from 54 African countries (1993–2020), researchers discovered that both gases significantly increase temperatures, with methane having a stronger effect. This warming then accelerates sea-level rise, threatening coastal communities.

Eastern Africa recorded the fastest growth in CO₂ emissions, while nearly all countries experienced warming, with Eastern and Central Africa heating up the most. Vulnerable coastal nations like Somalia and Guinea-Bissau face severe risks, including flooding and economic disruption. The study calls for urgent action: adopting renewable energy, improving waste management, and promoting sustainable farming. It also emphasizes the need for regional cooperation and increased funding for green projects to reduce emissions and protect high-risk areas. [Reference, Nature Humanities and Science Communications]

Abortion in Kenya: Rising Rates, Uneven Care: A 2023 national study by Kenya’s Ministry of Health, APHRC, and the Guttmacher Institute found that an estimated 792,694 induced abortions occurred, with a rate of 57 per 1,000 women of reproductive age–an increase from 2012. While unintended pregnancies have declined, over half now end in abortion. Post-abortion care (PAC) access has improved, with more women seeking treatment for mild complications, likely due to increased use of medication abortion, and life-threatening cases have dropped from 37% in 2012 to 1.4% in 2023. However, only 18% of primary-level facilities provide basic PAC and just 24% of referral facilities offer comprehensive services. [Reference, APHRC]

Phosphorus and Africa’s Food Future: Phosphorus is vital for growing food, especially in parts of Africa facing hunger. This study looked at how phosphorus was used in 53 African countries from 2000 to 2020. Although Africa has large phosphorus resources—mostly in Morocco—most of it was exported as raw material, with very little shared between African countries. Only a small portion was used for farming, and poor fertilizer use has worsened soil depletion in countries like Ethiopia. Africa also imports much of its phosphorus in the form of food. By 2050, better diets and reducing food waste could help lower phosphorus demand, but only more fertilizer use can fully meet future needs. Stronger cooperation across Africa is essential. Reference, Science Direct]

—END—