Climate Change and Africa’s Child Health Crisis

Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events are worsening hunger, spreading disease, and disrupting children’s daily lives in Africa

CREDIT: CHATGPT

On February 22nd, 2025 South Sudan closed all schools for two weeks due to extreme heat waves that caused students to collapse. The country’s Deputy Education Minister, Martin Tako Moi, stated, “an average of 12 students had been collapsing in Juba City every day.”

This was not an isolated incident. In March 2024, South Sudan had also closed schools indefinitely due to extreme heat.

As climate change accelerates, Africa’s youngest and most vulnerable face a growing crisis. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events are worsening hunger, spreading disease, and disrupting children’s daily lives, according to a perspective published in Nature Climate Change on March 3, 2025.

Almost 90% of the global disease burden linked to climate change falls on children, especially those under five. Despite contributing little to global greenhouse gas emissions, African nations are among the hardest hit, with children bearing the most severe consequences.

Food insecurity is one of the most immediate dangers African children face. Climate change has disrupted seasonal rains, leading to droughts in some regions and flooding in others, both of which devastate crops.

According to the perspective, 11.4 million children under five in the Greater Horn of Africa are currently suffering from acute malnutrition due to food shortages. Rising temperatures and prolonged dry spells have reduced agricultural yields, driving up food prices and limiting access to nutritious meals.

“Climate change increases the risks of malnutrition by affecting food production, and child malnutrition associated with seasonal food scarcity is likely to worsen as temperatures rise and rainfall decreases in Africa,” the authors state.

In South Sudan alone, 860,000 children under five are already affected by malnutrition, and extreme heat is making the situation worse.

A 2020 Lancet study found that “children living in hotter parts of sub-Saharan Africa are more likely to be wasted, underweight, and both stunted and wasted.”

Children can’t manage extreme heat

Similarly, a 2022 study in Science Direct focusing on West Africa found that if a child is exposed to very high temperatures (above 35°C) for an additional 100 hours per month over their lifetime, their growth (height-for-age) significantly decreases. Likewise, exposure to 30–35°C heat for 100 extra hours in the past three months reduces their weight-for-height.

The study also found that heat exposure has the most impact between 6 and 12 months of age, when babies start eating solid food and drinking water, increasing their risk of infections. High temperatures create ideal conditions for bacteria to grow in food and water, worsening child health.

Children are more vulnerable to heat stress due to their smaller body mass. “Their bodies heat up more quickly, and they have less ability to release heat through sweating,” says the Harvard Center on the Developing Child.

A climate model cited in the Nature Climate Change perspective found that child deaths due to extreme heat in 2009 were twice as high as they would have been without climate change. If global temperatures continue rising unchecked, heat-related child mortality could increase significantly in the next 30 years.

Beyond heat stress, higher temperatures and extreme weather are fueling outbreaks of vector-borne and waterborne diseases across Africa.

“Vector-borne diseases such as malaria have been linked to long-term climate change in Southern Africa and the East African highlands,” the Nature Climate Change study states.

Wildfires and industrial emissions, exacerbated by climate change, are making air pollution a silent threat to child health. Children exposed to both high temperatures and poor air quality face increased risks of asthma, bronchitis, and long-term lung damage.

Mental health and education

The impacts of climate change extend beyond physical health. The study highlights its growing mental health toll on children.

“Children will be increasingly exposed to high levels of trauma and stress during pregnancy and childhood, leading to changes in brain development and long-term cognitive and mental health issues,” the authors warn.

Climate change is also affecting education. As families struggle to afford basic necessities, many children—especially girls—are pulled out of school to help with household work or labor.

A study cited in the Nature Climate Change perspective found that in West and Central Africa, climate change disrupts education at all socioeconomic levels. Even wealthier households experience setbacks due to extreme weather events.

Floods and storms damage schools, leaving children without access to learning for long periods. In some cases, governments divert education funds toward disaster response and infrastructure repairs.

Climate change does not act alone—it worsens existing problems like poverty, poor housing, lack of healthcare, and conflict, making children even more vulnerable.

And in many areas, worsening economic conditions have forced children into child labor, early marriage, and migration as families struggle to cope. The decades-long war torn Somalia is a stark example of climate-driven displacement.

“Forced migration due to adverse climatic conditions has pushed Somali children into refugee camps in Kenya, where they face high risks of trauma-related disorders, malnutrition, disease, and premature death,” the Nature Climate Change perspective author's notes.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“North Africa contributes 50% of the global dust load…Emissions from North Africa account for 36%–79% of global dust emissions,” says Guidelines on Sand and Dust Storm Mitigation. But not all this dust is bad. “Deposits of mineral dust over land are also an important contributor to the fertilization of areas rich in vegetation. Mineral dust transported from West Africa, for example, is thought to fertilize the phosphorus-limited soils of the Amazon rainforest and thereby to increase primary productivity.”

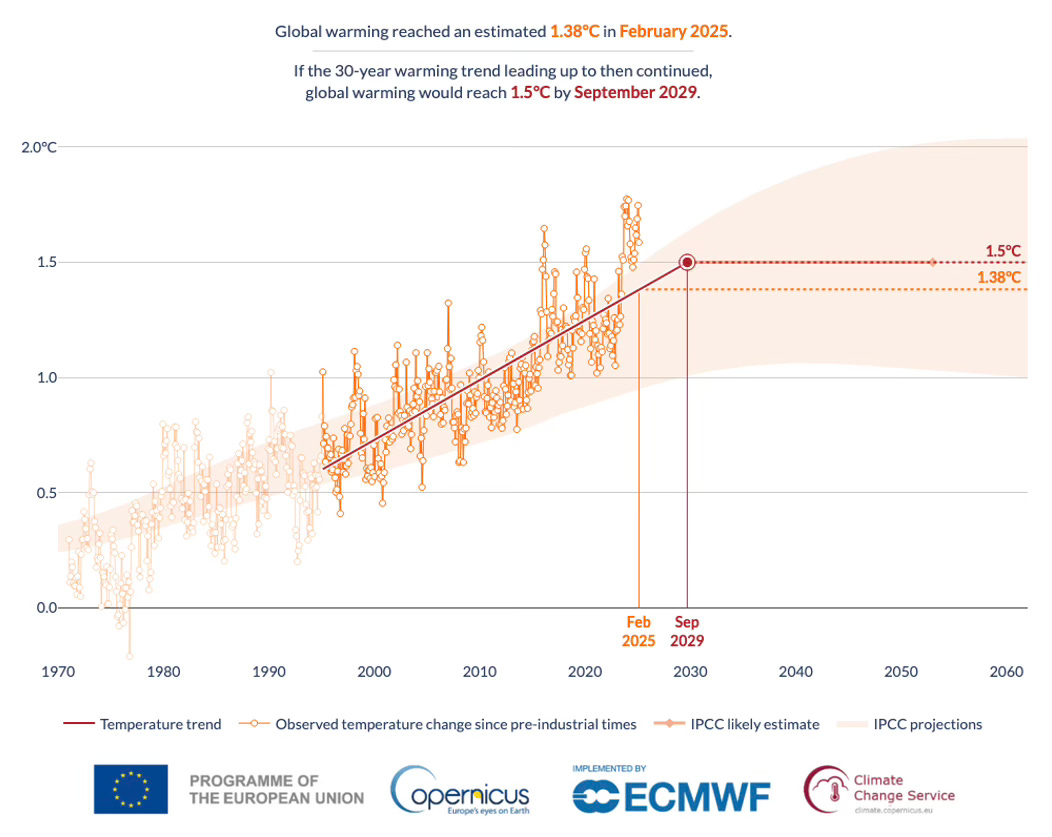

CHART OF THE WEEK

Heatwaves, droughts, flooding, food shortages, and hardship in coastal cities like Lagos and Mombasa—this is the reality Africa must brace for in a world warming past 1.5°C. When will the world reach 1.5°C? It could happen as soon as the next four years if global warming continues at the pace observed in recent decades, according to Copernicus data.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Machine Learning can make weather predictions better! Weather forecasts in tropical areas, especially in East Africa, often struggle to predict exactly when and how much rain will fall. This is a problem because heavy rain can cause flooding. Researchers tested whether combining Machine Learning with traditional forecasting methods could improve accuracy. By learning from satellite data, the new method reduced forecast errors, especially in predicting rainfall timing. [Reference, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems]

Food insecurity in pastoral communities of Ethiopia. Pastoralism has played a vital role in food security across sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Ethiopia’s Somali region, where hunger remains a pressing challenge. While pastoralism is essential for sustaining livelihoods, women face significant barriers that limit their full participation. To enhance food security, the study highlights the need to support pastoral communities, promote sustainable livestock farming, and remove gender barriers that hinder women’s contributions. [Reference, Nature Humanities and Social Science Communication]

Where did Uganda’s ebola come from? In January, Uganda announced an ebola outbreak. The index patient was a nurse who had not travelled out of Kampala, the country’s capital city. Scientists quickly studied the genetic makeup of the Ebola virus from the first patient. Their analysis showed that this virus is closely related to the strain from a 2012 outbreak in Luwero but is not connected to the 2022 outbreak in Mubende. This suggests the virus did not spread continuously from 2022 but might have come from an infected animal or another environmental source. Reference, Virological]

—END—