Critical Minerals, Critical Decisions: Why Africa Can’t Afford To Be Left Behind

Africa is at the heart of a critical mineral rush. It must seize this opportunity, or risk being sidelined in the very transition its resources make possible, we argue.

An artisanal miner holding a cobalt stone in Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit: Getty Images

You’ve likely heard about the Energy Transition—the urgent shift from fossil fuels to cleaner renewable energy like solar, wind, and hydropower. This shift is driving demand for critical minerals—like cobalt, lithium, and copper—that are needed for renewable energy technologies.

To make this transition possible, Africa must harness its vast wealth of critical minerals. The continent has what the world needs. What matters now is how it chooses to use it.

Take the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as an example. It's one of the most mineral-rich countries in the world.

Last year, while conflict raged in the eastern part of the country and as the world braced for a possible second Trump presidency, a significant event slipped under the radar.

Lawyers representing the country filed criminal complaints against Apple subsidiaries in France and Belgium. They alleged that Apple’s supply chain had been tainted with “blood minerals” sourced from the conflict zone in eastern DRC.

The complaint accuses Apple of profiting from illegally mined minerals laundered through global supply chains, all while promoting an image of ethical sourcing. Apple denies the allegations, claiming it holds suppliers to the highest standards.

In February, the situation in eastern DRC worsened as rebel groups seized two strategic cities. In a dramatic move, the Congolese president reportedly offered the Trump administration access to mineral reserves in exchange for military support. This highlights a troubling reality: the global battle for control over critical minerals essential to the energy transition is intensifying—and the frontlines are in places like the DRC.

The global energy shift

To limit global warming to within 2°C above pre-industrial levels, the world must drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions. Since energy production is a major contributor to emissions, this means transitioning to renewables like wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear power, while electrifying sectors such as transport and manufacturing.

This ongoing transformation--known as the energy transition--is the third major energy shift since the Industrial Revolution.

The first, from biomass to coal, powered European empires. The second, from coal to oil, propelled the rise of automobiles and mass manufacturing. Now, a transition from fossil fuels to electricity and hydrogen is underway–-poised to reshape the global economy once again.

Energy experts like Arnulf Grübler argue that previous transitions were marked by dramatic increases in energy consumption. The move from biomass to coal in the 19th century, and from coal to oil in the post-World War II era, both fueled global energy demand. This time, the surge is expected to be even greater–-driven by emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence, massive data centers, and electric vehicles, all of which require vast amounts of energy and resources.

This rising demand will put immense pressure on supplies of critical raw materials.

Africa, rich in these resources, stands at a crossroads: it can use this moment to develop new industries, create value locally, and shape its own economic future–-or remain a supplier of raw materials for others' prosperity.

Africa’s critical role and its vulnerabilities

The Global North’s accelerated shift to renewable energy has driven up demand for critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements. These minerals are essential for clean energy technologies—from electric vehicles to wind turbines and advanced battery storage.

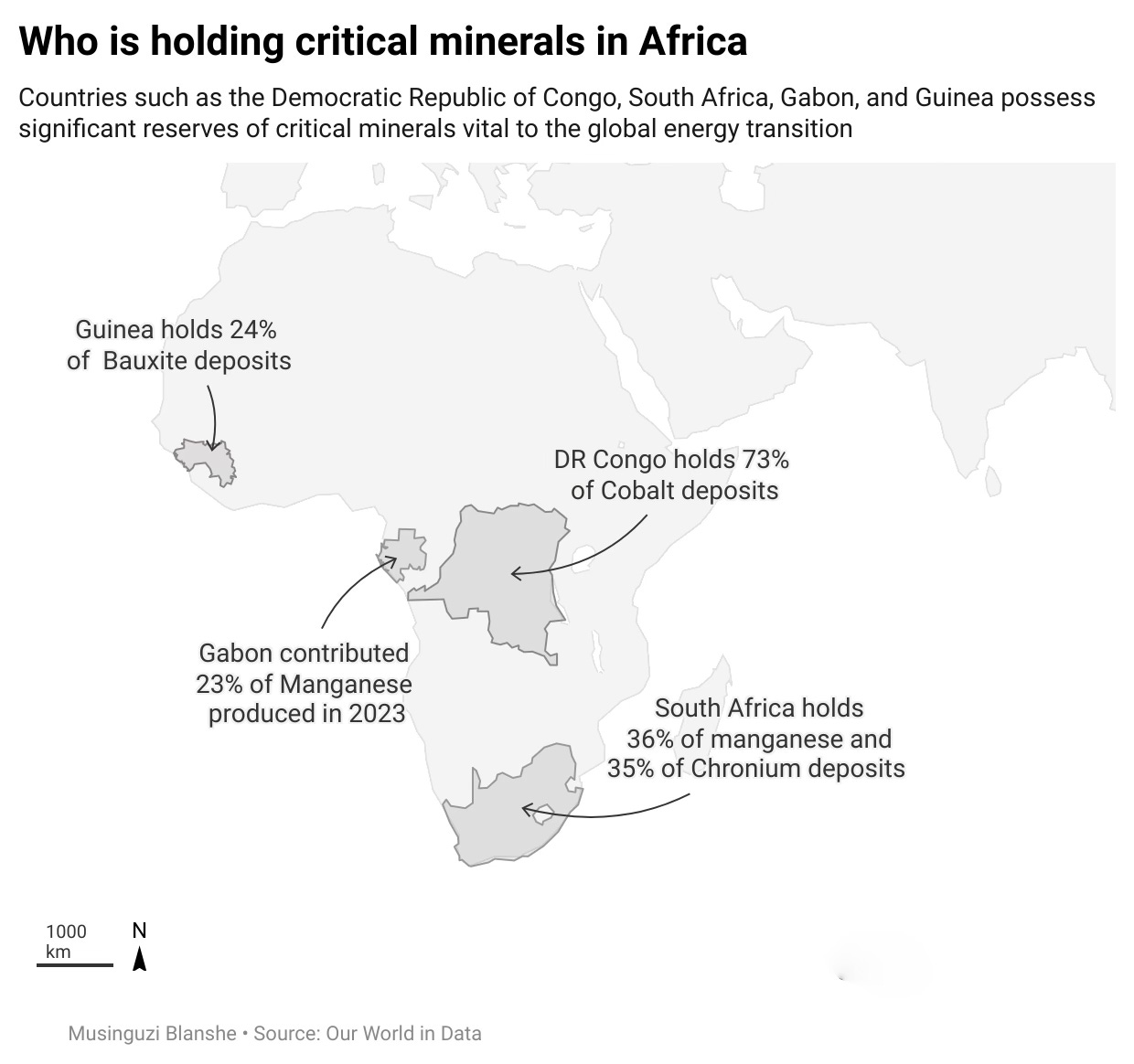

Africa is at the heart of this mineral rush. Countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zambia, South Africa, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe hold significant reserves of these strategic resources.

The DRC alone possesses between 60% and 70% of the world’s cobalt–an indispensable element in electric vehicle batteries. Meanwhile, Zimbabwe and Mozambique are home to vast reserves of rare earths and graphite, vital not just for clean energy, but also for modern defense and industrial technologies. It is estimated that Africa holds 30 percent of the world’s known critical minerals, including rare earths.

Yet despite this immense natural wealth, Africa remains at risk of being sidelined in the very transition its resources make possible.

Nowhere is this contradiction more stark than in the DRC. Although it supplies the vast majority of the world’s cobalt, less than 3% of it is refined locally. Instead, foreign companies extract the raw materials, ship them abroad for processing, and sell them back as high-value products. The Congolese people, like many others across mineral-rich African nations, see little of the economic benefit. “Local communities need a stronger say,” argues Rabah Arezki in Nature. Without bold investment in domestic refining and manufacturing, Africa could miss the energy transition’s biggest rewards.

This pattern–where Africa exports raw materials and imports finished goods–has long trapped the continent at the bottom of the global value chain. Without bold, strategic investment in domestic refining, processing, and manufacturing, Africa risks missing out on the most lucrative aspects of the energy transition yet again.

To shift this trajectory, African countries must not only protect their resource sovereignty but also invest in value addition at home–turning mineral wealth into industrial strength.

Africa isn’t in the requisite tech race

While Africa possesses many of the minerals crucial for the energy transition, it lacks the technical expertise, research and development (R&D), and industrial infrastructure needed to fully capitalize on this opportunity. The Global North has already positioned itself to dominate clean energy technologies, while Africa risks remaining a supplier of raw materials rather than becoming a producer of goods.

For example, in 2020, Chinese companies filed 84% of solar patents, 85% of wind, 78% of battery, and 75% of other electrification technology patents. Despite China’s lead, the race is still in its early stages, with Europe and the United States catching up. Africa's share in these green technologies is minimal—just 0.24%—with 84% of that activity concentrated in South Africa.

Africa can’t survive on oil

The stakes are also rising for Africa’s oil-dependent economies—such as Nigeria, Angola, and Algeria–as global demand for oil approaches its peak. These countries now face shrinking revenues and increased vulnerability. Unlike oil producers in the Middle East, who enjoy some of the world’s lowest extraction costs, African oil is significantly more expensive to produce–averaging $30–40 per barrel compared to just $5 in Saudi Arabia.

To make matters worse, while fossil fuels once generated substantial (if unevenly distributed) income, critical minerals—touted as the future of energy—offer far smaller and less reliable returns. In 2022, the global oil and gas industry earned $4 trillion in revenue, while the entire critical minerals market was valued at only $320 billion.

Crucially, an overreliance on exporting raw materials–whether fossil fuels or minerals–rarely leads to inclusive or transformative growth. Without a deliberate and coherent industrial policy, many African nations risk replicating past patterns: becoming extraction hubs rather than value creators. The danger is clear–trading one form of dependency for another, this time with fewer jobs, smaller revenues, and limited long-term benefits.

Critical minerals as a common good

Africa is at a crossroads. If the continent continues to rely on raw mineral exports without investing in downstream industries, it will remain vulnerable to external economic shifts. However, by leveraging its mineral wealth to attract joint ventures in refining and manufacturing, Africa could secure a stronger position in the global renewable energy market.

African nations must develop a coherent strategy for the energy transition—one that goes beyond supplying raw materials to actively participating in the renewable energy value chain. This could involve creating incentives for local mineral processing, investing in clean energy infrastructure, and fostering partnerships with technology firms to build local expertise.

This is where the example of the DRC’s proposed mineral deal with the United States becomes instructive. Rather than pursuing a bilateral minerals-for-protection arrangement, the DRC can leverage the collective bargaining power of regional organizations like the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and East African Community (EAC) to negotiate a broader trade deal–one that could transform its mining sector, create opportunities for neighboring countries to benefit from joint processing and infrastructure-related investments, and bring economic development to the entire Great Lakes region. The SADC and EAC blocs could also pull together resources to create processing industries for these critical minerals.

The DRC could also seek the expertise of pan-African institutions like the AfDB or Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) to provide advisory and technical support.

Such structured negotiations would help African countries coordinate their critical mineral policies, avoid a race to the bottom in mining deals, and hedge against the risk of “reprimarization” of Africa’s economy–an over-reliance on raw material exports at the expense of crucial sectors like manufacturing and value-added agriculture.

Countries like the DRC could also consider a bold strategy: banning raw mineral exports to force local processing. In 2020, Indonesia banned nickel ore exports, compelling foreign firms to build local smelters; today, it controls 50% of global nickel processing. A DRC cobalt export ban could achieve the same if backed by a serious industrial strategy that involves players like South Africa, which have a vibrant mineral processing industry.

The energy transition could be Africa’s leapfrog moment–but only if the continent moves from passive supplier to active player. Otherwise, history will repeat itself: the riches of the land will flow outward, leaving behind only the scars of extraction.

—END—