Fresh Look, Fatal Risk: The Truth Behind Africa’s Preserved Foods

A new scientific review says that food preservation in many African countries has taken a toxic turn—with harmful chemicals being used routinely to keep products from spoiling. Why?

CREDIT: CHATGPT

Across markets in Africa, food may look fresh and appetising due to preservation. Have you ever wondered whether the preserved food we consume in Africa is dangerous to our health due to chemicals used?

A new scientific review says that food preservation in many African countries has taken a toxic turn—with harmful chemicals being used routinely to keep products from spoiling. The study, published in Health Science Reports, questions whether this widespread misuse is a result of ignorance or something more sinister: intentional food fraud.

From fish laced with embalming fluid to vegetables treated with industrial pesticides, the report paints a disturbing picture of how unsafe chemical additives have become common in Africa’s informal food sector.

“Food preservatives are essential for preserving food, but their danger as ‘slow poisons’ increases the chance of illness or early death,” the authors write.

Food preservation is a necessity, particularly in Africa, where limited access to refrigeration and long distances from farm to market lead to massive food spoilage. In some regions, post-harvest losses can reach up to 40%, forcing vendors to find any means possible to extend shelf life. Unfortunately, this has opened the door to a wave of dangerous chemical practices.

In Nigeria, vendors have been reported using formalin, a chemical used to preserve corpses, to keep fish and meat from spoiling. In Ghana, the fat-soluble dye Sudan IV, known to be carcinogenic, is used to enhance the color of palm oil. In Ethiopia, bread is routinely treated with high doses of sodium benzoate—a preservative that, when used incorrectly, can form benzene, a cancer-causing substance.

“Formalin and some chemicals used for extending the shelf life of fruits can cause dizziness, weakness, ulcers, heart disease, skin disease, lung failure, cancer, and kidney failure,” the report notes.

These chemicals aren’t limited to meats or oils. Fruits like bananas and pineapples are artificially ripened using ethephon (also known as Ethrel), a plant hormone that can be toxic if misused. In some cases, even milk has been found laced with melamine—an industrial compound added to fake protein content.

Food fraud or lack of knowledge?

The researchers behind the study—experts from universities in Nigeria, the UK, China, and Japan—say the misuse of chemical preservatives in Africa falls into two broad categories: ignorance and food fraud.

In some cases, especially in rural areas, vendors simply don’t know the health risks of the chemicals they are using. They operate with little to no training and often rely on informal advice or trial-and-error methods to decide dosages.

But in other cases, the actions are deliberate. Unscrupulous sellers are knowingly adding illegal or excessive chemicals to boost profit, mislead consumers, and extend shelf life at the expense of public health.

“Food fraud… ultimately results in detrimental health effects,” the authors state. The line between ignorance and fraud can be blurry, but the public health consequences are clear.

Broken systems

One of the biggest contributors to the crisis is weak regulation. While countries like South Africa have relatively strong food safety frameworks, many others—including Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda—struggle with outdated laws, fragmented enforcement, and underfunded regulatory agencies.

In Nigeria, for instance, overlapping mandates between agencies like the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) and the Standards Organization of Nigeria (SON) often lead to confusion and weak enforcement. Corruption and lack of testing facilities also make it difficult to monitor markets effectively.

“Enforcing food safety rules in Nigeria is fraught with difficulties… hampered by inadequate budget, inadequate facilities, and corruption,” the report notes.

In Kenya, food safety oversight exists but doesn’t reach far beyond urban centers. In Tanzania, more than 50% of imported goods—including food—are reportedly fake or substandard, according to previous research cited in the study.

High stakes, low awareness

The health impact of these practices is far-reaching. The World Health Organization has linked pesticide residues in food to reproductive issues, developmental delays in children, and cancer. In a 2019 Kenyan study, 22% of fresh food samples contained pesticide levels above safe limits.

Other additives, such as synthetic dyes and preservatives, have been tied to allergic reactions, neurotoxicity, and gastrointestinal issues. Still, most consumers are unaware of the dangers.

“Africa’s food imports hit about 30 billion dollars annually,” the study notes, “and more than 50% of all goods, including foods, drugs, and other materials imported into Tanzania are reportedly fake.”

The researchers argue that the continent needs a coordinated and urgent response—not just from governments and scientists, but from communities, sellers, and consumers too.

Bottom line

This paper is a wake-up call—for you and me. Whenever you buy preserved food, always ask about the chemicals used. Make sure the people handling those foods are properly trained to apply those substances. That’s how we can start building a safer, healthier future for Africa’s food systems.

CHArT OF THE WEEK

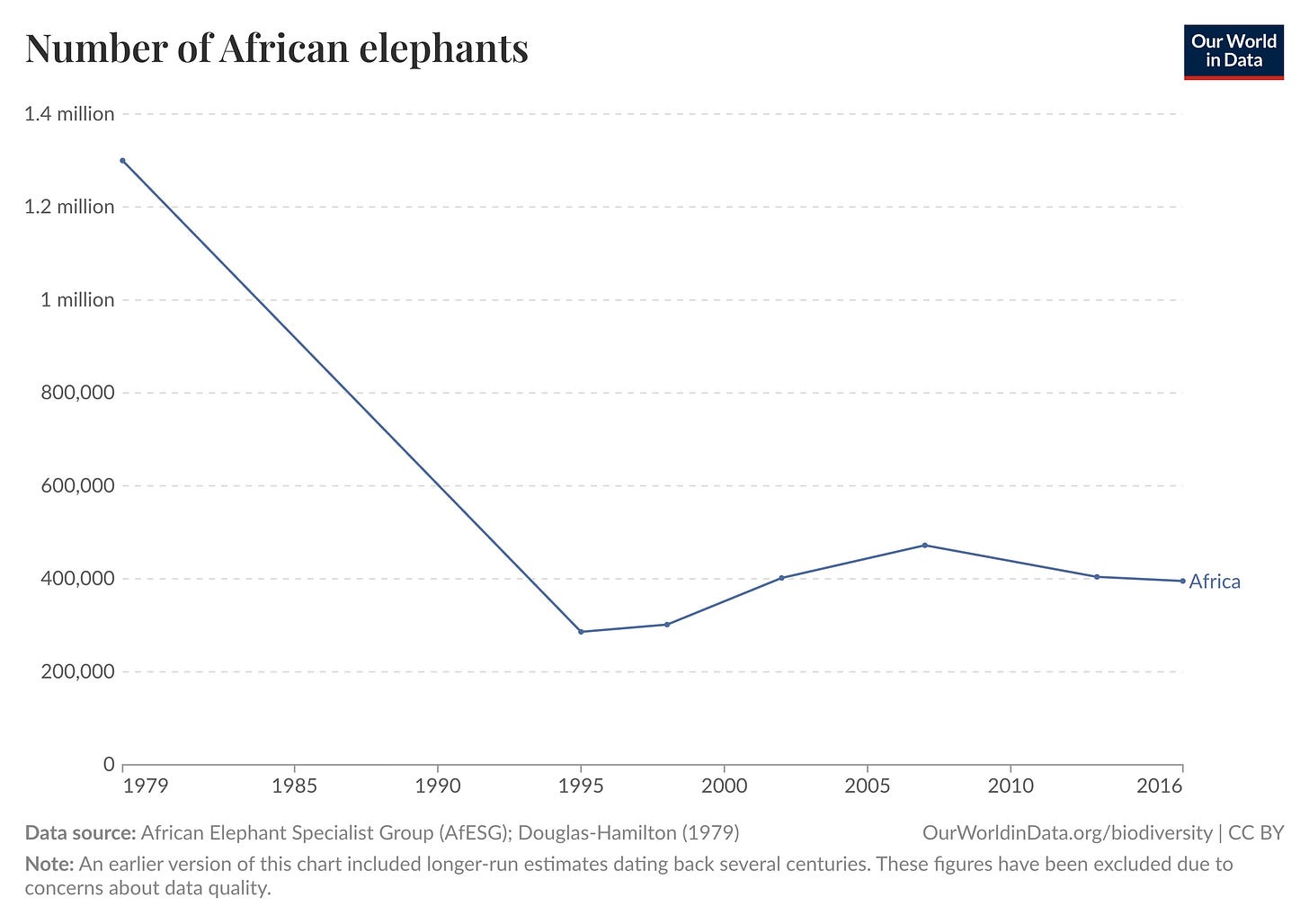

Did you know? The population of elephants in Africa has been declining primarily due to poaching for ivory, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict. Poaching remains the most significant threat, driven by demand for ivory in global markets, particularly in parts of Asia. Additionally, rapid human population growth has led to the expansion of agriculture and settlements. [See original chart]

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“And of the 5,000 to 7,000 research in the last decade on the continent, 60 to 80% of them are contained only in Egypt and South Africa. So the rest of the continent is to especially do research,” Dr. Mosoka P. Fallah, Africa CDC Acting Director for the Directorate of Science and Innovation on Africa’s Health Revolutions podcast.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Robotics in Africa, there is a bright feature: Robotics is perhaps not the first discipline that comes to mind when thinking of Africa. However, just as Africa has embraced its sister discipline, artificial intelligence (AI), robotics has an important role to play in the inclusive digital transformation of African economies. Today, it is having a positive effect on many sectors, from agriculture to medicine, education, and logistics. [Reference, Science Robotics]

Temperature and precipitation affect the water fetching time burden in Sub-Saharan Africa: In Sub-Saharan Africa, most households don’t have water at home, so people—mainly women and girls—spend time walking to collect it. A study using data from 31 countries found that weather plays a big role in how long these walks take. More rain makes water more accessible, reducing walking time, while hotter temperatures make it harder to find water, increasing the time spent fetching it. Rural areas are more affected than urban ones, but having electricity in rural communities helps reduce the impact. As climate change brings less predictable rainfall and higher temperatures, the burden of collecting water is likely to grow—unless access to both water and electricity is improved together. [Reference, Nature Communications]

Addressing mental health conditions in prisons in sub-Saharan Africa: People in prison across Africa are often overlooked in global mental health research and rarely mentioned in international health guidelines. Because there's so little information or support for mental health and drug issues in prisons, this study set out to find out what the top priorities should be. Experts from 27 countries (mostly in sub-Saharan Africa) were asked in a series of surveys what the biggest challenges are. They identified 38 key issues, grouped into areas like access to care during prison, support after release, the needs of women, the role of prison staff, and the overall prison conditions. The study suggests that improving mental health in prisons will require better-trained health workers, clearer policies, improved prison facilities, and alternatives to locking people up. [Reference, The Lancet Psychiatry]

—END—