Heat, Tech, and the Rural Body: A Pilot in Siaya-Kenya

What happens when wearable devices meet rural folks? A new study shows how high-tech tools can tell the hidden story of climate stress in rural Africa.

My first watch came as a gift from a friend about two months ago. Since I had never owned a watch before, I considered gifting it to someone else. But that didn’t happen. I’m glued to it–because it’s a smartwatch. It tracks my heartbeat, the steps I take, my sleep hours, and more.

More such gadgets are coming, and they are proving essential in how we deal with the effects of climate change. While they are still more common among the elite, the poor–especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, where people are highly vulnerable to climate extremes–also deserve access. Pilot studies on how low-income communities can use these tools are vital.

Someone is starting to do just that.

A recent pilot study published in npj Digital Medicine, conducted by a joint Kenyan-German research team, offers valuable insights into how heat affects rural populations in Siaya County, Kenya–and how acceptable these wearable technologies are to the people using them.

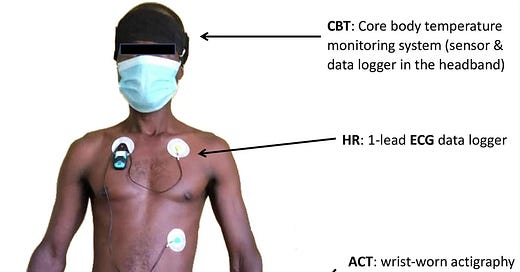

Using research-grade wearable devices similar to smartwatches, scientists monitored 48 farmers–half of them women–over 14 days to measure how their bodies responded to heat during daily life. These sensors tracked heart rate, core body temperature, sleep patterns, physical activity, and location. Environmental data loggers simultaneously recorded indoor and outdoor temperatures using a measure called the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT).

What emerged was a detailed physiological portrait of heat strain in rural Africa. Women, the study found, consistently experienced greater physiological stress than men. Their core body temperatures rose higher and stayed elevated longer. Their heart rates peaked earlier and remained above baseline during the hottest parts of the day.

On average, women recorded a higher Physiological Strain Index–a combined score of heart rate and temperature increases–than men. The difference, though modest in numbers, was statistically significant and telling: women are working harder under the same sun, and their bodies are bearing a heavier burden.

The reasons are complex. Both men and women engaged in similar levels of moderate to vigorous activity–averaging over 10,000 steps and 2.3 to 3 hours of movement daily–but women often sustained effort longer, especially during peak heat hours. Coupled with a lower heart rate reserve and slightly higher baseline body temperature, this increases their vulnerability to heat stress.

And despite all this exertion, sleep was not restorative. Both sexes recorded poor sleep efficiency–under 62%–likely due to indoor nighttime heat, which was often warmer than the outdoors.

But deploying these technologies wasn’t just a technical exercise; it was a test of social and cultural acceptance. Would rural farmers in Kenya trust and tolerate unfamiliar sensors on their bodies? The answer, overwhelmingly, was yes. Over 95% of participants rated the devices as likable and easy to wear. They reported minimal disruption to their routines, and none of the devices were lost or damaged during the study.

Even when some devices felt strange–especially the more noticeable headbands used to track temperature–most participants recognized their value. Still, there were gendered differences. Women were more likely than men to express concerns about certain devices, particularly the chest-worn monitors, which some found intrusive or cumbersome. They also attracted more public attention, as people asked questions about what they were wearing.

Despite minor discomforts, participants embraced the broader purpose of the study. They understood that these devices were not just gadgets, but tools to tell an important story–one of rising heat, stressed bodies, and the urgent need to adapt. Their willingness to participate reflected not just curiosity but a sense of collective responsibility and benefit.

This study comes at a critical moment for Sub-Saharan Africa, which is warming faster than many other regions. Outdoor workers–especially smallholder farmers–are on the front lines. Unlike mechanized agriculture in wealthier countries, farming here relies on manual labor. With little access to shade, cooling systems, or rest infrastructure, these farmers face growing risks of heat exhaustion, dehydration, and long-term productivity losses.

The data from this pilot study lays the groundwork for targeted interventions. For example, the insight that heat peaks between 2–3 p.m.a, a time when farmers are often still in the fields, suggests that promoting work pacing or shifting heavier tasks to cooler morning hours could significantly reduce physiological stress.

This kind of information can help farmers adjust their working hours to avoid dangerous heat exposure. It also shows that the future of climate adaptation may be wearable, data-driven, and inclusive.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

Mozambique has been battling a cholera epidemic. For the week ending May 3rd, it reported more cases than all other countries with cholera outbreaks. Read Africa CDC report for more details

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“Malaria transmission is expected to shift in sub-Saharan Africa, with both increases and decreases in malaria suitability depending on the region. Climate models indicate that areas traditionally at risk might see declines in malaria transmission, but new regions–particularly at higher elevations or in previously cooler zones–could become malaria hotspots,” The Lancet Planetary Health [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(25)00051-8/fulltext]

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

How Rising CO₂ Affects African Rainfall, It Depends on the Climate: A study that looked at how rising carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels affect African monsoon rainfall found that the impact depends heavily on the overall climate. When the climate is warm–like it is today–increased CO₂ mostly boosts rainfall by adding more moisture to the air (a "thermodynamic effect"). But in colder climates, CO₂ tends to reduce rainfall by weakening the wind systems that drive the monsoon (a "dynamic effect"). Using climate models that simulated both warm and cold historical periods, researchers discovered that CO₂ can either increase or decrease rain depending on which effect is stronger. This finding shows that the same greenhouse gas can have very different outcomes based on background climate conditions, which is important for predicting how future global warming may shape rainfall–and food and water supplies–across Africa. [Reference, Geophysical Research Letters]

New House Design Cuts Indoor Mosquitoes by Over Half: A study found that a new mosquito-proof house design reduced malaria-carrying mosquitoes indoors by 51% and nuisance mosquitoes by 61% compared to traditional homes in rural Tanzania. These "star homes" featured screened windows, self-closing doors, smaller eave gaps, and elevated bedrooms, which together helped block mosquito entry. The homes also stayed cooler at night, encouraging better use of bednets. However, the study showed that leaving doors open in the evening still allowed mosquitoes in, highlighting the importance of behavior alongside design. With millions of homes expected to be built across Africa, including mosquito-proofing in new housing could greatly reduce malaria risk. [Reference, The Lancet Planetary Health]

Mimicry in Motion: How Elephants Play and Connect A study which examined how African Savanna elephants communicate found that these animals can quickly mimic each other’s trunk and head movements during play, often within one second. This behavior, known as Rapid Motor Mimicry (RMM), helps elephants coordinate their actions, especially in competitive or rough play. Elephants that mimicked more were also more likely to start playing after watching others play, suggesting that playful behavior can spread through the group like a shared mood. Surprisingly, age, sex, and how close the elephants were socially didn’t affect this mimicry. The findings suggest that elephants may be able to share emotional states during play, offering new insights into how empathy may have evolved in social animals like humans.[ Reference, Nature Scientific Reports]

Chimpanzees Use Stones to Communicate in a Culturally Unique Way: in Guinea Bissau, researchers observed wild chimpanzees using stones to hit tree trunks—similar to how they use their hands and feet to drum on trees. This stone-assisted drumming appears to serve as a form of long-distance communication, possibly linked to male displays or group coordination. The behavior shows unique patterns compared to hand/foot drumming, suggesting it might have a different purpose. Since the practice varies across locations and is repeated by individuals, it may be a culturally learned behavior—one of the rare examples of animals using tools for communication rather than food-related tasks. [Reference, Biology Letters]

—END—