One century, one truth: humans came from Africa

I am extremely excited to publish the first edition of this newsletter. This is a learning platform, and I hope you will find it exciting and gain valuable insights from it. I look forward to reading.

The Taung Child fossil

February 2025 marks one hundred years since the groundbreaking research on discovery of the Taung Child, the skull of a young human-like ancestor found in South Africa.

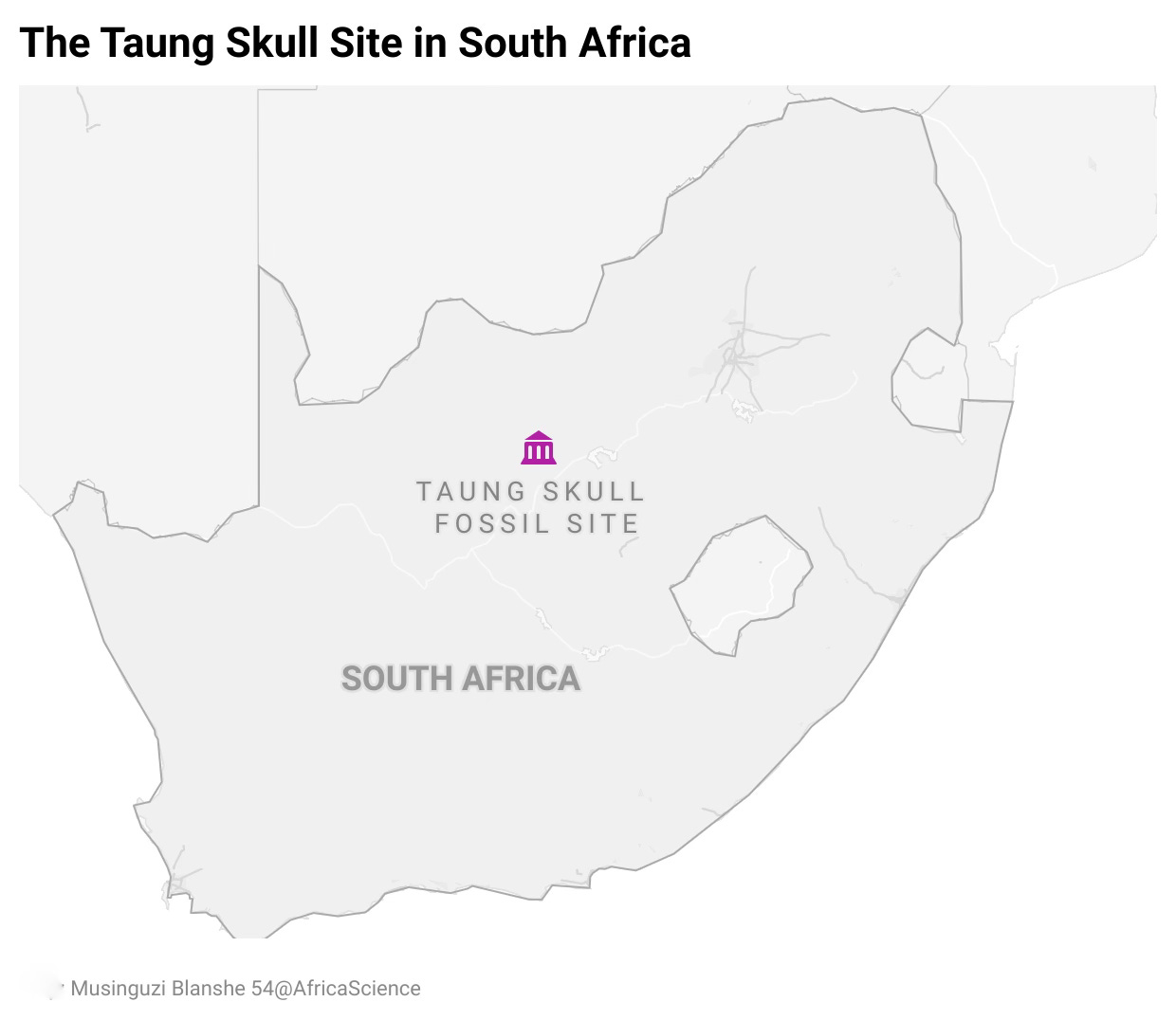

The skull was named after Taung, a small town in North West Province of South Africa, where it was discovered. It was first identified by anatomist Raymond Dart, who was teaching at the University of the Witwatersrand. A network of Black miners and local researchers played a crucial role in excavating and delivering the skull to Dart from Taung, which is located more than 400 km from Johannesburg.

The skull belonged to a child who lived about 2.8 million years ago, placing Africa at the center of human origins. Dart published his findings in a paper titled "Australopithecus africanus: The Man-Ape of South Africa" in Nature in February, 1925.

To mark this centenary of human origins research in Africa, Nature published a collection of articles, while the South African Journal of Science released a special page edition.

This article is drawn from the highlights of the South African Journal of Science edition.

Dart’s findings were initially dismissed by many European scholars, who were influenced by the now-debunked Piltdown Man—a fake fossil that misled scientists for decades–by falsely suggesting that early humans evolved in Europe. However, Dart’s discovery was ultimately vindicated in the 1950s when the Piltdown Man was exposed as a fraud.

Dr. Emma Mbua of the National Museums of Kenya, the lead author of a paper in the special edition titled "Palaeoanthropology in Kenya: After the Discovery of the Taung Child," says the Taung Child discovery was a turning point for human origins research in Africa.

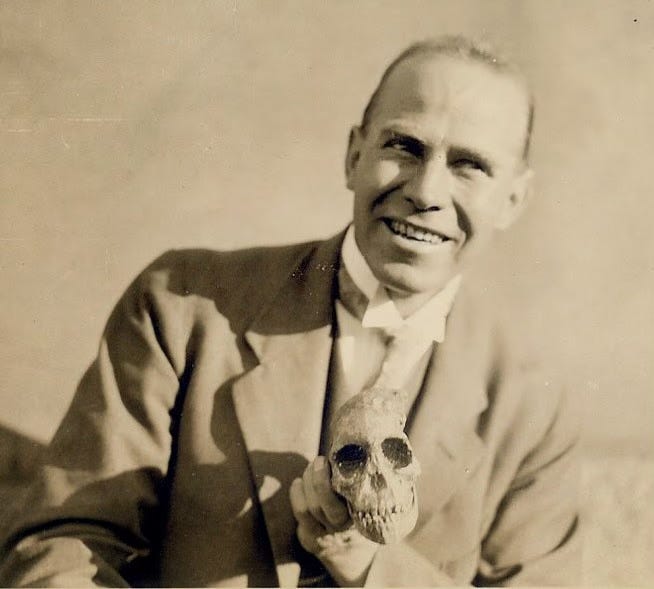

Photograph of Raymond Dart holding the Taung skull

“This discovery not only confirmed Darwin’s theory that human origins lay in Africa but also led to the systematic exploration of fossil sites across the continent,” she notes.

It inspired Louis and Mary Leakey to search for more ancient human ancestors in East Africa. Their efforts led to the discovery of key fossils, including early human-like species in the Great Rift Valley. Today, East Africa is known for having some of the oldest and most diverse remains of early humans ever found.

The study of human brain

Another paper in the special edition, titled "Looking for the Origins of the Human Brain: The Role of South Africa in the History of Palaeoneurology," highlights how the Taung Child played a crucial role in studying how ancient brains evolved and how humans developed thinking and cognitive abilities.

Dr. Amélie Beaudet, the lead researcher, explains that the Taung Child helped answer major questions about human brain evolution.

“Dart initially suggested that the Taung Child’s brain displayed a human-like reorganization, but later studies challenged this claim, proposing that its structure was more primitive than originally thought,” notes Dr. Beaudet and colleagues.

The skull contained a natural imprint of the brain, which sparked discussions about how early human ancestors thought and functioned. Over time, new technologies like 3D imaging have allowed scientists to study these brain imprints in greater detail than ever before.

By comparing ancient brain imprints from fossils found in South Africa with modern human and primate brains, researchers have gained new insights into the development of language, intelligence, and brain functions.

From exclusion to leadership

Despite these scientific breakthroughs, African researchers have faced significant challenges in the field. Dr. Emma Mbua and colleagues examined the historical difficulties that African scientists have encountered. For decades, human origins research in Africa was largely dominated by Western scientists, with local researchers often excluded from leadership roles.

However, there is hope. Recent efforts, including training programs and increased investment in local scientific institutions, are helping to shift this dynamic.

“The field of palaeoanthropology must move beyond its colonial legacy,” said Dr. Mbua and her co-authors. “African scientists should lead research on their own continent, ensuring that discoveries benefit both science and local communities.”

One major initiative driving change is the Turkana University College’s new MSc program in Human Evolutionary Biology, the first of its kind in Kenya, which is fully funded for Kenyan students. Programs like this are equipping a new generation of African scientists to take charge of research in their own regions.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“We have 84% of the US global health investment coming to Africa and we can imagine that there is no doubt that Africa will be the most affected,” Dr. Ngashi Ngongo, Principal advisor to the Africa CDC Director General and the Continental Incident Manager for mpox

STATISTIC OF THE WEEK:

February 10th was the deadline for countries to publish their new emissions-cutting plans, known as "nationally determined contributions" (NDCs). In Africa, only Zimbabwe submitted its NDC on time. Globally, 95% of the world's countries missed the deadline.

NEWS HIGHLIGHTS:

Lenny Rashid Ruvaga, a Kenyan journalist, writes in the Harvard Public Health Review how Kenya is exploring traditional medicine as a cost-effective way to fill gaps in diabetes care. With cases rising and insulin beyond the reach of many, researchers are working to validate plant-based remedies and waiting for the Kenyan government to create new policies.

Musinguzi Blanshe, author of this newsletter writes in Aljazeera how Uganda is battling a new ebola epidemic which has come with lack of information due to pushback by the tourism industry. The industry has argued that too much information about the outbreak is bad for the economy.

Linet Owoko, writes in Daily Nation that Kenya has introduced the single-dose human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, replacing the previous two-dose regimen, to increase the chances of protection against the virus and related diseases such as cervical cancer.

Javier Guzman and Sophia Greenhoe look at which countries in Africa will feel the biggest impacts of US aid suspension. They put US support in context of countries’ own incomes, and how much support they received from other donor countries.

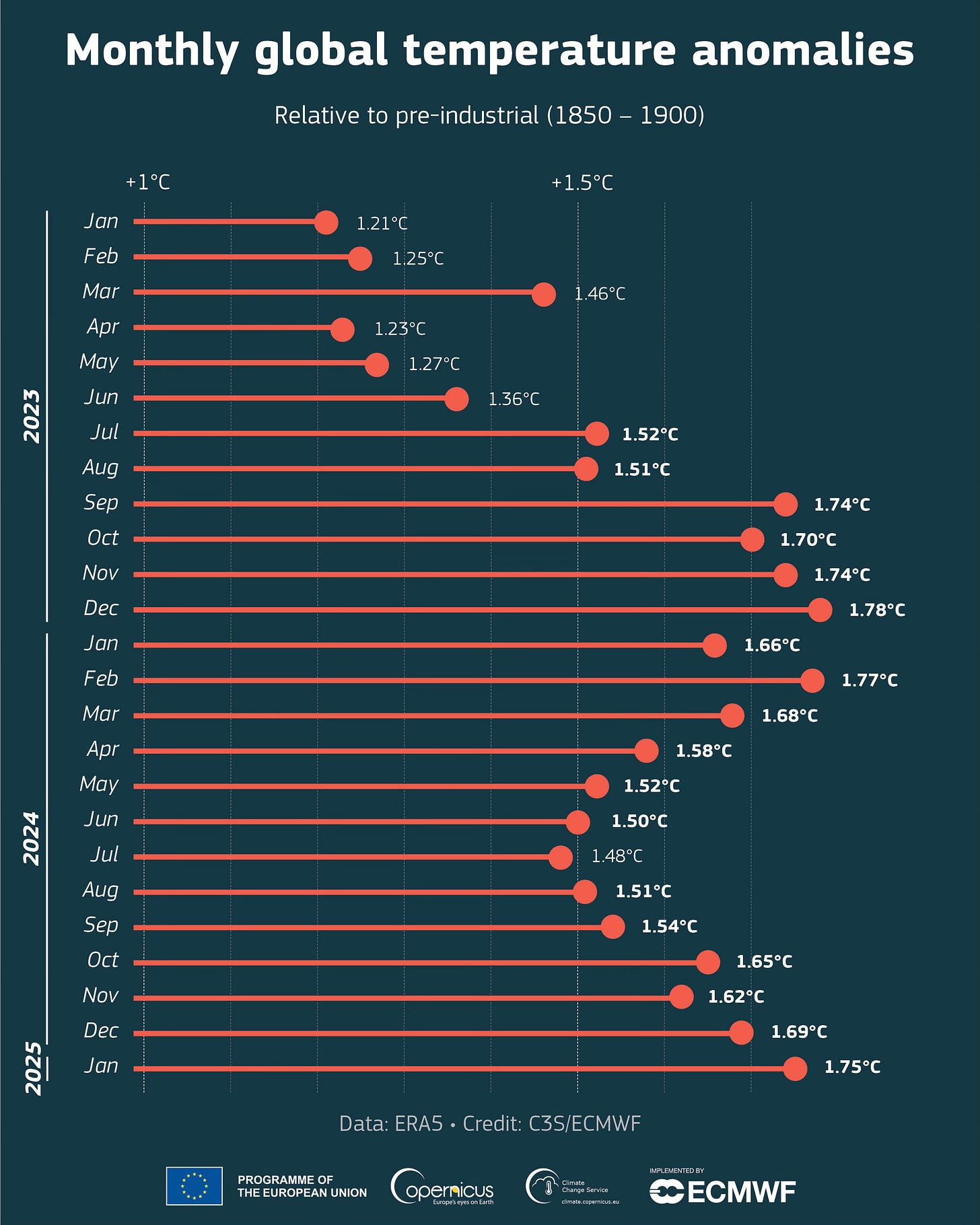

GRAPH OF THE WEEK

The world is heating up! For all but one month in the past 19 months, the global temperature has averaged more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS:

Frances M. Cowan and colleagues, writing in Nature Medicine, note that HIV incidence is declining globally, but nearly half of all new infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa—where adolescent girls and young women bear a disproportionate burden. For those at risk, the authors emphasize that interventions strengthening motivation, capabilities, and access to all available HIV prevention technologies are critical—not only for adolescent girls and young women but also for broader epidemic control.

Fanglin Guan and colleagues, in PeerJ, assess the quality of life among African medical and health science students at the International University of Africa (IUA) in Sudan. Their findings indicate that dentistry students reported a significantly higher quality of life, while students aged 20–23 years had better social relationship quality of life. However, second-, third-, and fourth-year students recorded lower social relationship scores.

Xueye Wang and colleagues, writing in Nature Communications, examine how strontium isoscape—a method of tracing geographic origins—is aiding in identifying the origins of sub-Saharan African victims of the transatlantic slave trade. The slave trade story is well documented, however, archaeologists and historians have long struggled to pinpoint the specific geographic origins and individual life histories of enslaved individuals within the African diaspora.

END