What do we learn from an ancient Egyptian’s DNA?

Sequencing the DNA of a man buried in a pot has uncovered a genetic map of ancient migration, linking early Egyptians to Morocco and Mesopotamia over 4,500 years ago.

More than 4,500 years ago, in the early days of Egypt’s pyramid age, a man was buried inside a giant ceramic pot, tucked into a rock-cut tomb near the banks of the Nile.

Today, his bones sit in a museum in the UK but his DNA is telling a story that spans continents and millennia.

For the first time ever, according to a paper in Nature, scientists have managed to sequence the full genome of this Old Kingdom Egyptian man who lived during the time when pharaohs were just beginning to build their mighty pyramids and establish one of the longest-lasting civilizations on Earth.

The breakthrough offers not only a glimpse into the ancestry of early Egyptians, but also hints at ancient migrations that may have shaped one of the most iconic societies in human history.

And it all started with a man in a pot.

The remains were uncovered in Nuwayrat, a burial site near Beni Hasan, some 265 kilometers south of Cairo. The man had been buried in an oversized pot, a practice typically reserved for high-status individuals in early Egypt. He was placed in a rock-cut chamber, a burial style consistent with the Old Kingdom’s royal cemeteries.

But even though his burial was grand, his body told a different story.

He stood about 157 to 160 cm, and by the time he died, he had lived a long life by ancient standards–around 60 years old. His teeth were badly worn, and his bones showed signs of severe osteoarthritis, especially in his spine and joints.

“He experienced an extended period of physical labour, seemingly in contrast to his high-status tomb burial,” the scientists wrote.

They even suggested–based on wear patterns and comparisons to ancient Egyptian art–that he may have been a potter.

Cracking his DNA code

Extracting ancient DNA is always a challenge, especially in hot and dry environments like Egypt. But something about this pot burial helped preserve the man’s genetic material. From seven of his teeth, scientists managed to extract enough DNA to reconstruct his entire genome–a first for anyone from this early period in Egypt.

And the results were fascinating.

The majority of his ancestry–about 78%–came from ancient people living in North Africa, particularly from a population in Neolithic Morocco. These early farmers lived around 4,500 BC and are thought to be descendants of both local African hunter-gatherers and immigrants from the Levant–modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine.

But the other 22% of his DNA pointed eastward–toward Mesopotamia, the region that includes modern-day Iraq, and a cradle of early human civilization.

This shows that people weren’t just trading objects or ideas like writing systems or domesticated plants. They were also migrating, leaving a biological footprint in Egypt’s gene pool even before the pyramids went up.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9918576/

No genetic connection to Sub Sahara Africa

This isn’t surprising. A 2022 study that looked at how people from south of the Sahara Desert mixed with those in North Africa over the past several centuries found similar hints.

Although the Sahara has mostly acted as a barrier between the two regions, trade and slavery–especially during the trans-Saharan slave trade–brought people from sub-Saharan Africa into North Africa.

By studying the DNA of modern North Africans, scientists have found small amounts of genetic ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. This suggests that gene flow across the Sahara did occur, though on a smaller scale.

For instance, a 2018 study that sequenced the DNA of individuals buried about 15,000 years ago in Morocco found that two-thirds of their ancestry was linked to ancient Levantine populations while the remaining one-third traced to a mysterious sub-Saharan African lineage, most closely related to modern West Africans.

What Did the Egyptian Man Look Like?

Using genetic markers, the researchers predicted that the man had brown eyes, brown hair, and dark to black skin—a typical appearance for people living in the Nile Valley. His sex was confirmed genetically as male, matching the physical features of his skeleton.

The team also tested the chemical makeup of the man’s teeth and bones to learn more about where he lived and what he ate. These isotope studies revealed that he grew up in the hot, dry climate of the Nile Valley, eating a diet typical of early Egyptians: grains like wheat and barley, and meat or fish, likely from the Nile.

“All results are consistent with having grown up in the hot, dry climate of the Nile Valley… and consuming an omnivorous diet based on terrestrial animal protein and plants,” the researchers reported.

In other words, he was born and raised in Egypt, but his DNA remembered older stories of distant migrations and ancient blends of people.

VISUAL OF THE WEEK

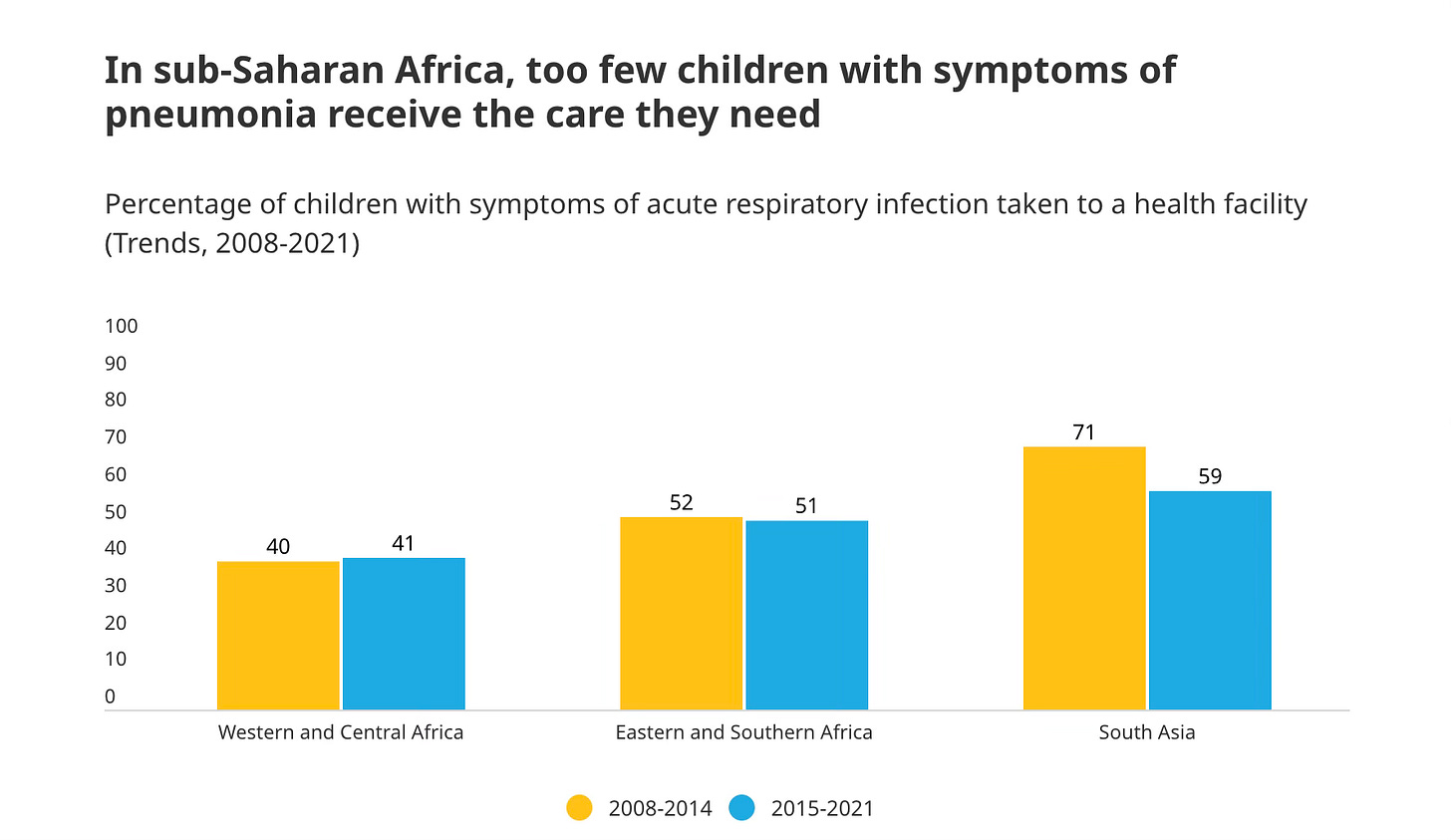

In sub-Saharan Africa, where the most pneumonia deaths occur, only around 50 per cent of children with acute respiratory infection (ARI) symptoms are taken for care. Read more here

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“While the International Finance Corp. [IFC] has made public promises to improve health care for everyone, its financing for private hospitals in East Africa has instead deepened inequality. It has also contributed to the tens of millions of dollars in management fees and financial performance bonuses paid to private equity firms for their work managing investments in hospitals on behalf of the IFC and others,” Ben Dooley and Micah Reddy for the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Read the investigation here.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS

Ancient Proteins Reveal Africa’s Lost Wildlife: Scientists have discovered that tiny proteins locked inside fossilized teeth can survive for millions of years, even in the hot, harsh climate of East Africa. In this study, they extracted enamel proteins from animal fossils found in Kenya's Turkana Basin, some dating back 18 million years. These proteins, preserved in tooth enamel, helped identify ancient species like early rhinos, elephants, and hippos, and confirmed their evolutionary links to modern animals. The research proves that enamel is a powerful time capsule, preserving biological information long after DNA has decayed. This breakthrough allows scientists to explore the deep past of African mammals and trace how different species evolved, offering a new way to study extinct life in regions where DNA rarely survives.[Reference, Nature Communication]

Lake Victoria Basin Soil Losing Nitrogen: A study of the Lake Victoria basin shows a 7.2% drop in soil nitrogen between 1996 and 2015, threatening food security for the region's growing population. Using over 3,000 soil samples and machine learning, researchers found nitrogen levels fell from 503 to 467 grams per square meter, causing a total loss of 6.6 million tons—worth an estimated $21.5 billion. Farmlands were the most affected, while forests saw slower declines unless cleared. Losses were highest in the south, with richer nitrogen zones in the northeast and southwest. The decline is linked to factors like fertilizer use, GDP, temperature, and soil type. The findings highlight the need for better land management to protect soil health and support sustainable farming. [Reference, Land Degradation and Development]

Abortion Laws Linked to Low Birth Control Use in Africa: A study in sub-Saharan Africa found that women in countries with restrictive abortion laws were less likely to use modern contraceptives compared to those in countries with liberal laws. Only 1 in 4 women used modern methods, and fewer than 1 in 10 used highly effective options like implants or sterilization. However, countries with supportive adolescent contraceptive policies and higher health spending saw greater contraceptive use. The study suggests that restrictive abortion laws may limit both safe abortion and access to birth control, increasing the risk of unintended pregnancies. It recommends reforming abortion laws and expanding access to effective contraception to improve reproductive health outcomes and protect women’s rights across the region. [Reference, PLOS Global Public Health]

—END—